By Lewis Finney

The UK is currently in the midst an election that is considered by many to be one of the most important in living memory. With the future of the NHS, relationships with the EU, and societal issues such as homelessness and foodbanks all in the public’s focus, reliable information and trustworthy leaders should be of paramount importance to the electorate. Unfortunately, the integrity of both are questionable at best.

The integrity of politicians aside, the world we live in today can easily be infiltrated by propaganda, misinformation and disinformation. Social media platforms offer little in the way of fact checking political advertisements, often designed to intentionally mislead targeted would-be voters, so aimed at due to their perceived malleability.

Suggestions that the Brexit referendum and Donald Trump’s successful US presidential campaign both had outside influencers organising the spread of disinformation only compound this as a worrying contemporary issue, but what does the future hold in this respect?

Technology is changing the way that we consume media. As it inevitably advances in sophistication and usability, the more commonplace certain product become in our world. Take smart watches as an example – only in the last half of this decade have they become an item that we’re used to seeing on people’s wrists.

So, what’s next?

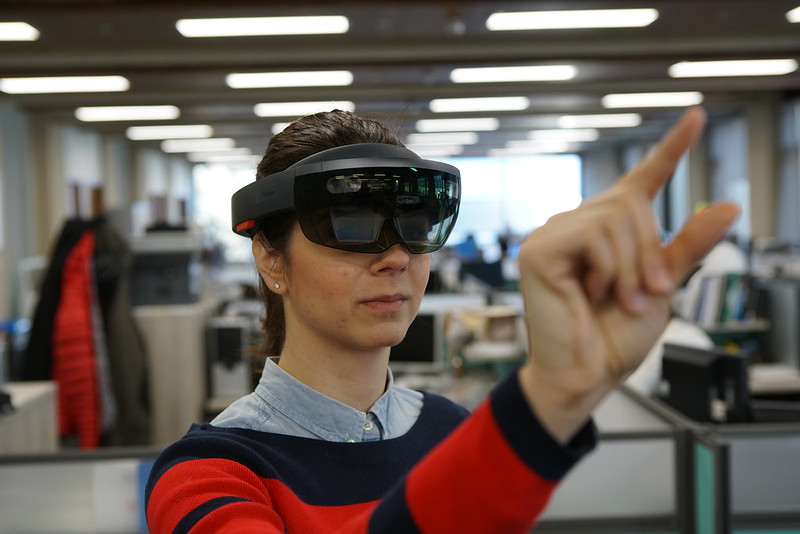

In the technology industry, many expect that the next wearable device is likely to be spectacles with augmented reality and virtual reality capabilities. It’s frequently rumoured that Apple might have some to share with the world in the near future, although the date is perpetually being put back.

VR and AR technology is readily available and the big players in the technology industry are already involved. Those in the industry perceive it to merely be a matter of time before we’re all used to seeing the glasses as commonly as we now see smart watches.

Once the technology is widely available, it’s inevitable that industries across the board will be scrambling to make use of AR and VR, and with that, the way we consume much media will likely become immersive experiences.

Photo: Engineering at Cambridge (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Saleem Khan is a career journalist and founder of immersive and spatial technology consultancy, JOVRNALISM, based in Toronto, Canada. He sees immersive technologies as an essential part of the future of journalism and wants to open the world’s eyes to its potential.

“I look at it as an essential domain in which journalists and news organisations need to get involved because immersive and spatial media is going to be the dominant means by which we engage with information, probably within a decade,” Khan said.

Immersive technologies will not only change the way we consume media, but the way our brains engage with the material is also different

Khan said: “It’s not the same as looking at a screen, it’s not the same and reading some text, it’s a different type of interaction because a different part of your brain is active when you are immersed in an experience.

“When you’re consuming media in a more traditional sense you actually have intellectual filters that provide some distance from that, but when you’re immersed, the part of your brain that’s active is the same part of your brain that’s active as you go about your day and you experience the world. It records the things you experience as actual memories, not as information that you’re storing.”

Despite the exciting possibilities that this new way of experiencing information possesses, there also lies an alarming issue. Imagine a general election in ten years’ time, when Khan expects this technology to be readily available. If the issues surrounding misinformation and disinformation haven’t yet been addressed these unscrupulous tactics are still being used as legitimate political strategies, the potential to effectively control the minds of voters is a real possibility. If people can be swayed into voting a certain way by a targeted Facebook advert now, the potential for misuse when the information is consumed as an experience and committed to memory is far more disturbing.

“You have to be aware of the impact you’re having on the people who are consuming what you are producing.

“It is extremely difficult, maybe impossible to convince someone that something they have experienced is not real. Even though we know that immersive and spatial media are created experiences, that still doesn’t change that fact that the way that your brain responds to it is as if it’s real,” Khan said.

Politics seemed like the obvious, most topical choice to apply this to, but it could truthfully be enacted in any number of ways by those who would wish to manipulate us.

Part of Khan’s mission is to identify this potential problem and to stop it before it becomes just that: “If we’re at the point where immersive and spatial media has disinformation being produced, and the infrastructure for it doesn’t have any verification or authentication aspects to it then we have a real problem because what we’re doing then is creating a world both for virtual reality and augmented reality where the understanding of a reality in fact becomes highly malleable,” he said.